“The problem is that while physics has had its Newton, its Einstein, and its quantum mechanics, economics is still waiting for its scientific revolution.” — Paul Krugman

“Economics is not about goods and services; it is about human choice and action” — Ludwig von Mises

I’ve always been fascinated by economics, in fact before I started writing about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, I wrote a lot about economics including in the media for a variety of venues.

I’m not a trained economist, though. I’m actually a data scientist, because I saw the writing on the wall about the dawn of a self-accelerating age of AI and robotics, and I realized that I needed to train myself in that field. But even in the AI age, I still find myself preoccupied by economic questions.

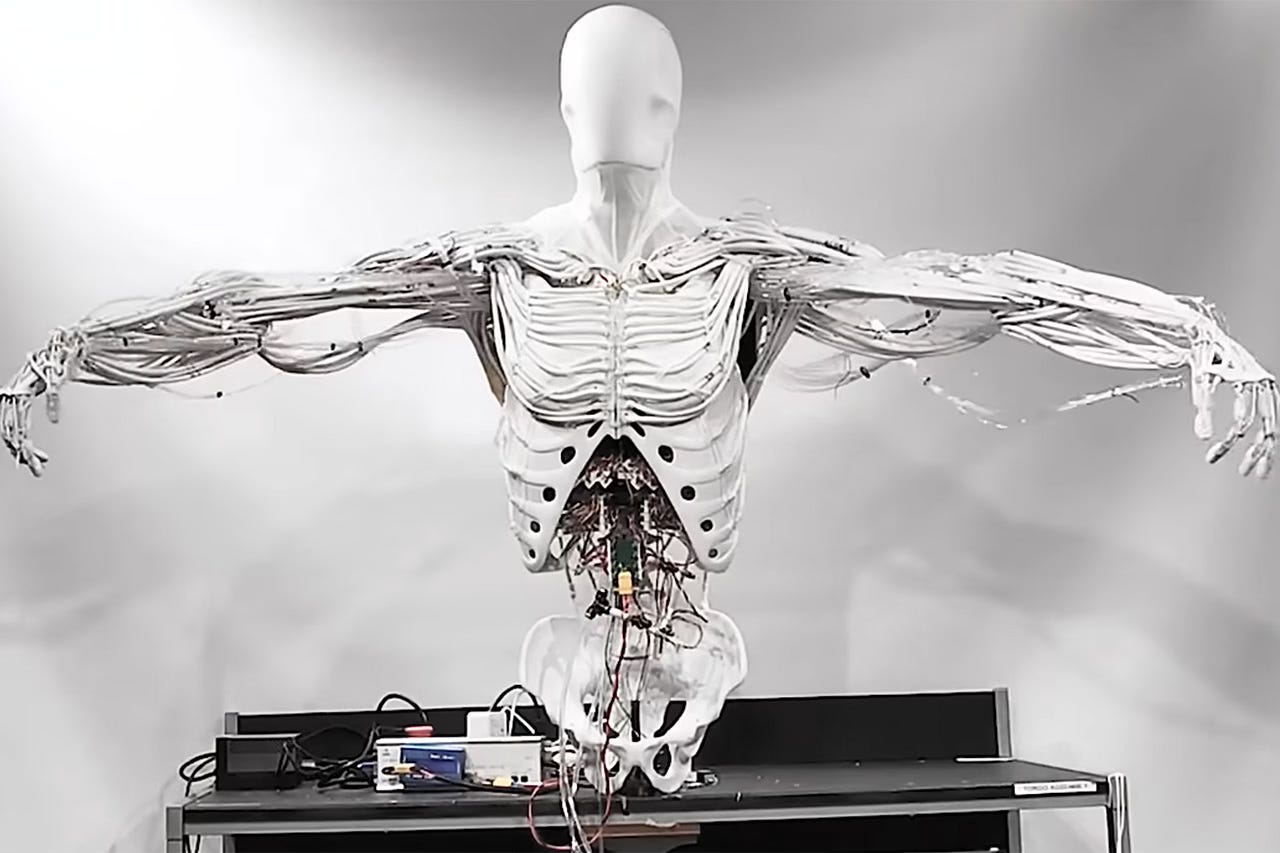

What will people do when AI agents—including those wearing corporeal robotic bodies to interface with the physical world—can do the majority (and perhaps a great majority) of the jobs faster and more cheaply than humans?

History tells us that assuming that there are a fixed quantity of jobs to go around—and thus that automation will create permanent unemployment—is a fallacy, better known as the lump of labour fallacy.

For a while, at least, as I wrote for Quillette earlier this year, I would expect that the norm will be that humans will still work, not as labourers but as the directors of the machines. We will commandeer AIs and robots in our wake as we build out our world.

But this is a transition where machines will be able to self-repair, build more machines, and self-accelerate, or what we refer to as the Singularity. As AI gets more and more refined, it will require less directing. Certainly, highly motivated or visionary people will still be able to do this. If you want to colonize Mars or the moons of Jupiter, there’s a lot still to do.

But for the majority of us, do we just sit back and enjoy the robopocalypse and simply transition to forever-funemployment?

I very much doubt it, for one main reason—I think unemployment tends to be dysfunctional and maladaptive.

Paul and Moser (2009) found that unemployment significantly increases psychological distress, depression, and anxiety. Long-term unemployment is associated with lower self-esteem and higher suicide rates.

Now, obviously, these studies occurred before the Singularity. Maybe after the Singularity people will happily wake up, strap on a VR headset or lay down in front of a 100-inch OLED screen and rot the day away playing Fortnite 2 on their PS7. Or develop an addiction to ketamine, or whatever.

But—and this brings us to the fundamental question here—that doesn’t seem very economical. You see, economics (as Mises correctly noted) is not so much about goods and services. Human relationships to goods and services are just an expression of economics. What economics is actually about is how intelligent beings express our desires through our behaviour.

In the era of artificial general intelligence and artificial superintelligence—much of it arising from non-transparent black-box style models like large language models—economics is no longer just about human desires. It becomes about machine desires. Now, the obvious counterpoint to this is that machines desire whatever humans program them to design, and that is true up to a point, but again with black-box models that self-improve, we don’t really know how they will desire to interact with the world. Presumably a lot of their desires will be extensions of the human corpus—simply because they have been trained on our civilisation—but we don’t really even know that, either.

The question of how intelligent beings express our desires through our behaviour is never going to have a fixed answer. As the Post-Keynesian economist Hyman Minsky noted—and this is such an important point that is going to have to be reiterated many more times in the coming centuries—stability is destabilising.

Intelligence is a fundamentally disruptive trait. Intelligence is the ability to listen to a dogma, and question it, or reject it. Intelligence is the ability to see something far away, and react to it, to interact with it, sometimes in strange and unpredictable ways.

Now, I know that most people are quite predictable, and operate within a fairly narrow band of behaviours. That’s probably because many of us have observed empirically that highly-experimental and novel actions can have unpredictable consequences for us, and this is compounded by evolution. To our tribal ancestors, the risk-takers who tried the mysterious berries oftentimes ended up vomiting or comatose or dead.

But sometimes our intelligence gets the better of us, and we become counterintuitive, rebellious, or contrarian.

The economics of the future will see a continued experimentalism that will take us to many weird and peculiar places, while also bringing us great comfort and luxury. Humans—and our machine cousins—will remain mysterious and a bit unpredictable.

But at least as a science, we are developing a structure for data gathering, data processing, and data analysis that will allow economics to try to make sense of this all. In many ways, we have taken great strides in this in recent years, and I say this as someone who spent large chunks of the last few weeks messing around with various financial APIs in Jupyter Notebooks. There are lots of amazing and free data sources that anyone who knows how to code can deploy.

While intelligence is a fundamentally disruptive trait, intelligence equally demands that we try like hell to make sense of the world, and to make sense of each other. Being able to predict others’ behaviour is as profitable in war-time as it is in peace time. It’s how you win at games with a player-versus-player element, like chess, and Pokémon, and Street Fighter. It’s how you position yourself to take advantage of the predictable elements of the world.

Just as Minsky said that stability is destabilising, I would add the counterpoint that instability is stabilising. That’s the fundamental tension at the heart of the economics and the wider social sciences. Instability, for many of us—maybe even the majority—is scary and off-putting. But what’s more this turbulence can strengthen us to work to find ways to stabilise our wider world. A country or region being ravaged by fighting between various groups might be highly motivated to stop the violence. That leads to progress.